Family history has a way of collapsing centuries into a single line on a chart. Names repeat. Dates stack up. Then occasionally, one of those names turns out to belong to someone who changed the country.

Recently, my oldest daughter has become interested in family trees, genealogy, and has always fancied history. I know my grandmother has said we were related to this historical figure before, but I had not traced it myself yet. We worked on this yesterday and quickly found our connection.

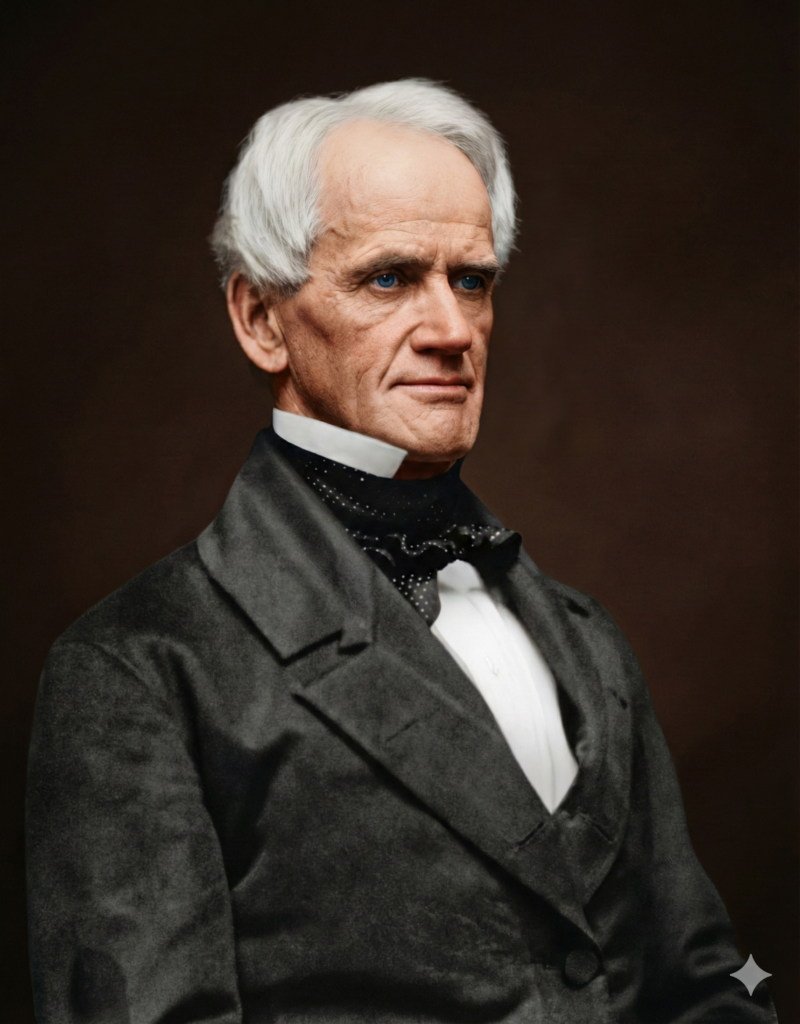

So let’s talk about Horace Mann.

Horace Mann, born in 1796 and died in 1859, is widely known as the father of the American public school system. He was a political reformer, educator, and social thinker whose work shaped how education functions in the United States to this day. What makes that history more personal is that Horace Mann is my third cousin seven times removed.

Who Was Horace Mann?

Horace Mann served as the first Secretary of the Massachusetts Board of Education. At a time when schooling was inconsistent, underfunded, and often unavailable, he pushed for the idea that education should be free, universal, nonsectarian, and professionally taught.

He believed education was a stabilizing force for democracy. His annual reports argued that an educated population reduced crime, strengthened civic participation, and created economic opportunity. Many of the norms we now take for granted, standardized school terms, trained teachers, and common curricula, trace back to his advocacy.

His influence extended well beyond Massachusetts. His ideas helped shape public education across the United States, and his legacy still shows up in debates about access, equity, and the purpose of schooling.

The Shared Ancestor

The family connection runs through Samuel C. Mann, born in 1647 and died in 1719.

Samuel C. Mann is the common ancestor shared by Horace Mann and my own direct line. From that point, the family splits into two branches that unfold over the next two centuries.

On Horace Mann’s side, the lineage runs:

Samuel C. Mann, Thomas Mann, Nathan Mann, Thomas Mann, and finally Horace Mann.

On my side, the lineage runs:

Samuel C. Mann, William Mann, Elijah Mann, Obediah Mann, Fisher Mann, Aaron Mann, Amos Mann, Oliver A. Mann, Virgil A. Mann, William B. Mann, James Mann, and then me.

That difference in generational distance is why the relationship is described as third cousin seven times removed. The cousin number reflects the shared ancestor. The removal count reflects how many generations apart we are.

As detailed in Mary Peabody Mann’s ‘Life of Horace Mann’ (1865), his parents Thomas and Rebecca instilled resilience amid hardship, echoing our shared ancestor William Man’s colonial endurance.

Why This Matters to Me

It is a reminder that history is not abstract. The people who shaped institutions were not carved from marble. They were members of families, part of long, ordinary lines of people who farmed, migrated, argued, failed, adapted, and occasionally left a mark large enough for textbooks.

It also highlights how thin the distance really is between past and present. Twelve generations sounds vast, but on paper, it fits on a single screen.

A Living Line, Not a Footnote

Family history is often treated as trivia, a list of names preserved for curiosity’s sake. But when one of those names belongs to someone whose ideas still shape daily life, the exercise changes character. It becomes less about claiming connection and more about understanding continuity.

Horace Mann did not emerge in isolation. He came from a lineage that extended backward through colonial New England and forward into the present, carried by people whose lives never entered textbooks but whose existence made his possible. The same family tree that produced a national reformer also produced farmers, laborers, parents, and migrants, generation after generation.

Seen that way, ancestry is not about proximity to greatness. It is about scale. Individual lives ripple forward in uneven ways, sometimes quietly, sometimes loudly, but always connected. Tracing that connection does not elevate the present. It grounds the past.

And it reminds us that history is not something we stand outside of. We are already in it.

Read more about what I have to say about AI on my Substack.